"You need to grasp the nettle"

Niklas Fanelsa on commoning, bioregional architecture and why beauty matters

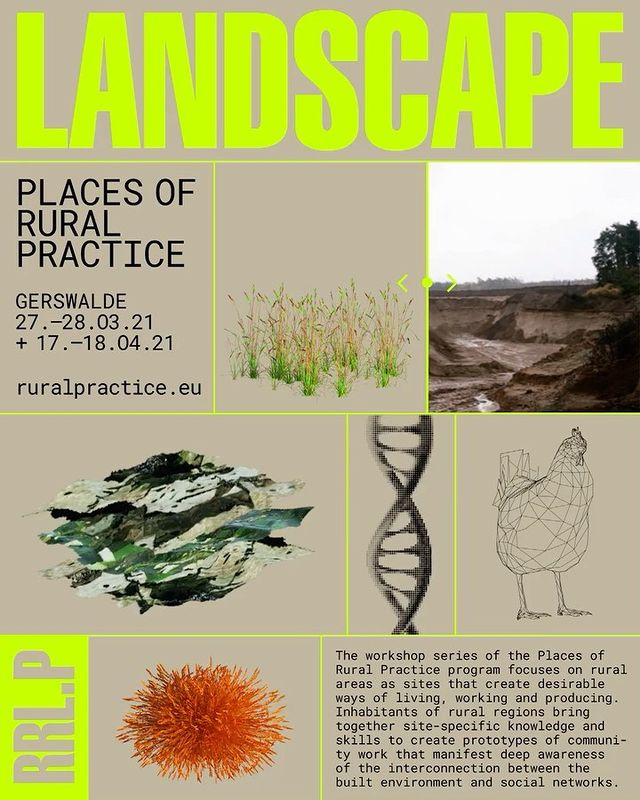

“In the age of the polycrisis, the city is not providing many answers. We urgently need to shift towards a regenerative approach, and the countryside can be an ideal testing ground for these new practices”

says Niklas Fanelsa, founder of Atelier Fanelsa, an architecture practice based in Berlin and Gerswalde, a small village in the German countryside.

I came across their work a few years ago and was intrigued by their thoughtful approach, paying acute attention to the rural context they’re operating in.

Atelier Fanelsa are not about grand gestures. They tread lightly. Through practical and meaningful interventions, they shift the usage or perception of a space, fostering greater community engagement and cultural exchange. All while making ‘work in progress’ look extremely aesthetically pleasing.

Niklas initially got exposed to working in the countryside while studying in Japan. Together with his fellow students, he spent several weeks in a rural area fully immersed in everyday village life, getting a holistic understanding of the territory and local practices. This turned out to be an influential time. When he started out in a saturated market in Berlin, he felt his competence was not needed in the city. At the same time, there was not much focus on the countryside.

Today most of Atelier Fanelsa’s projects are public buildings in rural areas, something Niklas is quite proud of.

“Five years ago, no architect from the city would have wanted to do these projects. I see more potential for impact in designing these small-scale community spaces in rural areas.”

But getting there was a long process. Atelier Fanelsa has been working in Gerswalde for four years. Now the practice is slowly starting to implement innovation. Thinking long-term is crucial. “It's not that we turn up in the village, show a PowerPoint and everybody is on board.”

Something that the studio can contribute to in these rural locations is bringing awareness to what is already present, and drawing attention to what might have been overlooked. “We say, for example, look, you have a very nice old clay building. You could reuse the old clay bricks and turn them into new plaster.” This understanding of context and resources can create a new sense of identity for the community.

For Niklas, the countryside offers a welcome counterpart to the ‘professionalised’ environment of the city where most people are super focussed on one thing. As I argued in one of my previous posts, there is opportunity to pursue a greater diversity of activities. The periphery can provide people with space and time to be more experimental. Rather than planning a concept from beginning to end, and then executing it, there is room for trial and error. Feedback loops are faster and more direct. Residents can respond immediately to a new material or community space.

“The nice thing about architecture is that we are physically present. People can see the result. There’s an artefact and we can have a conversation about it. Then we make the next artefact. It is important to take small steps.”

With this incremental approach, a concept can be continuously improved and adapted. The process becomes more interactive, allowing the local community to get involved. This creates a sense of belonging, an integral element of ‘commoning’ – a particularly passionate topic for Niklas.

So what exactly is commoning? It’s the self-organised social practice of building and maintaining shared resources (“the commons”). These can include anything from materials, natural features, and building traditions, to craft techniques, as well as values or policies. At its heart is the practice of collaboration and negotiation. It involves speaking to your neighbour and working out a compromise, something we increasingly struggle with. As Emerging Curator for the Canadian Centre for Architecture Niklas developed a series of workshops around this idea of shared stewardship. This approach plays a central role in the transition towards regeneration.

“Now everything needs to be contracted and be precise on paper. We have unlearned to engage in these kinds of neighbourly relationships. I'm interested in designing systems that facilitate commoning, a more holistic social practice.”

Niklas is a big advocate of bioregional architecture, which takes a territory’s natural resources and living systems into account. It demands a much more tailored and localised approach. “It's not something you can order in a catalogue.”

Bioregions are geographical areas defined by climate, soil, flora and fauna and transcend national borders. A bioregion in Germany might be similar to another bioregion in the US or Japan, enabling a transnational knowledge exchange between those regions. However, the exchange of goods and energy should happen in close proximity. Transport costs and emissions are still not priced into the development of architectural projects.

“We need to acknowledge that it doesn't make sense to import material from Portugal to northern Germany when we have an equal material or craftsmanship in the area, but maybe at a slightly higher price.”

Next to his practice, Niklas teaches architecture at the Technical University of Munich. Rather than lecturing his students about using regional wood, he takes them to the nearby forest for a more embodied learning experience. They get the opportunity to cut down a tree, interact with forestry professionals, and, above all, see, smell and feel the trees.

“Once they’ve had this immersive learning, they view a forest with different eyes. I think this embodied knowledge is important to enable transformation.”

It’s an educational approach we desperately need more of. I’m also curious about the mindset of his students. Where do they want to live, or work? Do they feel they need to be in a city to have a career?

“Many young architects still dream of a big project in the city. Our current system of the capitalist market economy is aiming at centralisation. That means for architecture, offices will get bigger and more centralised.”

Yet, there are so many abandoned villages and existing structures in the countryside that are vacant, while living space in cities is increasingly unaffordable. It feels like a no-brainer for emerging architects to seek out more work in the periphery, but still, the shift seems slow.

Niklas can detect a strong need for security amongst the younger generation. It is understandable that people long for stable employment and income in today’s volatile environment. In his role as professor, Niklas tries to support the students to become more daring.

“I like the phrase ‘grasping the nettle’ [to force yourself to be brave and do something difficult or unpleasant]. You need to embrace venturing into unknown territory sometimes. I try to provide a framework, and instil confidence in the students.”

In his opinion, many disciplines are focussing too much on the past to make predictions for the future. We need more imagination for something new to emerge. And sometimes that means starting a process without knowing where you will end up.

“Imagination is not a soft, fuzzy skill. Conceptualising and designing something in the future is an ability that can be very precise. It helps to convince others to follow your path.”

I agree. Imagination is a powerful tool, and we need to relearn how to engage with it urgently. We end our conversation on the topic of beauty.

“In architecture, you are trained to find proportions in floor plans or facades that are beautiful. But I think beauty can also exist in other things. A business plan can be beautiful if there is a good relationship between the people who are connected to it. A product is beautiful if it considers the people who make it and its environmental impact. We focus too much on the facade of things, and not enough on the inside. There's an opportunity for designers and architects to find beauty in systems and relationships.”

Learn more about Atelier Fanelsa here

Read Niklas’ essays on rural commoning here

Loved this article .The fact that he is encouraging his students to look into rural areas whereby people have moved away because of job prospects etc . To think about ways to regenerate them again for the good . Friends I knew from many years ago . Students at the AA (architects association) who were way ahead of their time . Created many projects like these . City Farms, solar panels etc etc . Maybe they weren’t way ahead , maybe society & the World were well behind . Too little & hopefully not too late . I want my grandkids to have a wonderful future. Teach future generations the good stuff. .💚 .

I’ve never heard the term “grasping the nettle” before. I wonder if it comes from the fact that nettles have create an unpleasant stinging sensation if you grasp them the wrong way. Rumor has it that if you don’t feel the nettle’s sting that means you’re a witch, but I digress.