Whenever I read trend reports about ‘the home of the future’ tech plays a central and dominant role. In the so-called smart home digital technology is seamlessly integrated into every corner of the home. It’s an AI-enabled space where mundane tasks are outsourced and automated (the smart fridge reorders items we’ve run out of), leisure time is enhanced with gamified, immersive experiences (think VR goggles for the whole family) and living rooms are cosy, sedative cocoons (adapting lighting and temperature to our personal preference) sheltering us from the harrowing world outside. Everything is optimised for convenience, comfort and safety for the consumer (and surveillance/value extraction for the corporations providing it).

This vision doesn’t sound very smart to me. Not only is it incredibly dull, it’s also totally disempowering. I believe we’re placing way too much emphasis on comfort. And don’t get me started on convenience. A service that offers people to deliver a single avocado to their doorstep in less than 10 minutes simply should not exist. Where is this all headed? Are we never going to leave the house again? Never interact with other humans again? It’s not like increasing levels of comfort and convenience is making us happier or healthier. Quite the opposite. We’re the most depressed, anxious and chronically ill we’ve ever been.

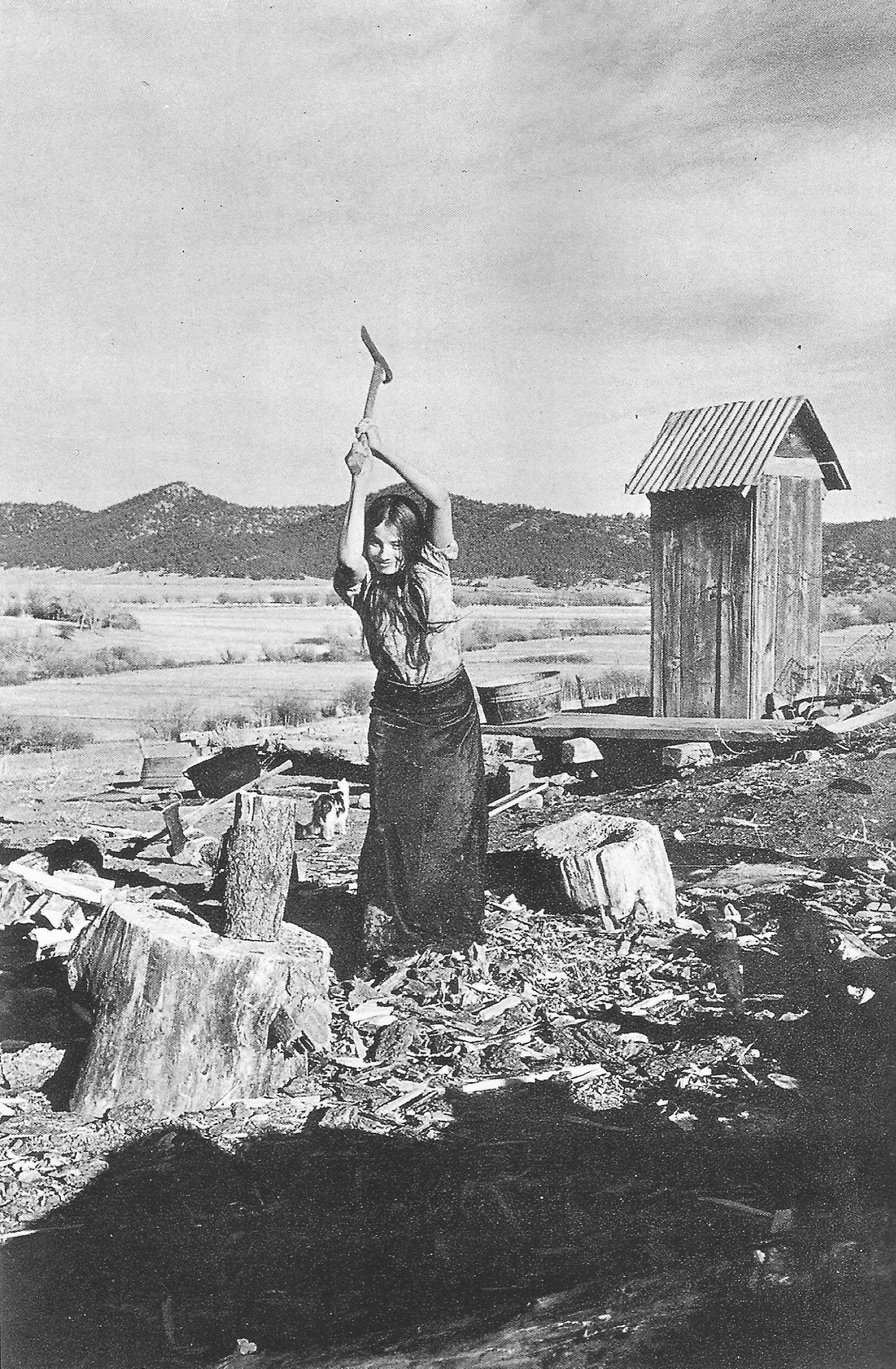

Still, we are allowing tech to colonise every single facet of our lives. This hyper-digital life takes us further away from ourselves and the embodied experience. Outsourcing the most minuscule tasks and equipping our homes with tech-heavy products that require an internet connection for basic functionality further amplifies our dependence on systems that are already strained to breaking point. It might be counter-intuitive, but to handle the upheavals caused by climate breakdown that are going to be more intense and more frequent, we need to let go of our obsession with comfort and convenience. Only by exposing ourselves more regularly to discomfort are we going to strengthen our resilience. And don’t we crave it, too? Don’t we all want to feel more alive and live more intensely? To create environments in which humans can truly thrive, we need to be guided by different principles than just comfort and ease. A small first step would be to become a little more self-sufficient again. Learning how to solve shit by ourselves and within our communities will help us to reclaim some level of agency.

So what would an alternative vision for the home of the future look like?

I think some clues are to be found in the past. In the pre-industrial era, the domestic dwelling was where most work took place. From shoemakers to blacksmiths or scholars, skilled workers made things out of their homes. Food was produced within or around the house. This was all part of life – making, mending and feeding oneself. The duality of life and work hadn’t been established yet.

In post-industrial societies, the domestic space has the potential to become a place of production again. Since the pandemic working from home is the norm for many, at least for some days of the week. It looks like this hybrid model is here to stay. This again allows for greater flexibility and the integration of more diverse tasks into our ‘work life’. It enables us to make some things for ourselves again, and however small, this might give new meaning to our lives.

As climate pressures are increasing and geopolitical conflicts are having tangible effects on global supply chains, a more self-sufficient lifestyle has become aspirational again. Even as an optimist, it’s hard to ignore the mess we’re in. The World Economic Forum speaks of ‘new and rapidly evolving sources of risk that will reshape the next decade’ and ‘a deteriorating global outlook’. Dark Matter Labs who help create institutions and infrastructures for a more equitable and caring future, frame their work ‘against a systemic backdrop of steadily declining foundational systems of civilisation’. And cultural critic Shumon Basar believes ‘the unwinding of colonial modernity is underway and accelerating’. The compound risks we’re facing today are hard to underestimate, but already in 1976 E. F. Schumacher wrote in the foreword of ‘The Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency’:

“What if there is a hold-up, a breakdown, a strike, or unemployment?”

Greater self-reliance not only makes sense, it can also make us more content. A crucial element for me is turning the home into a place of production again (and I don’t mean productivity!). My vision of a truly smart home is one where some sort of knowledge work is done to generate part of the income, in tandem with some food production and preservation. It is a place for a multitude of activities, a place where we can acquire practical skills like gardening, woodworking or sewing. This home of the future is one of reduced complexity, a place filled with fewer things, but things we know how to care for and repair. It is a place that connects us to the outside, the weather, the seasons, also when that’s not always comfortable. Maybe it stimulates us to spend more time outside. Digital technology has its place, but we’ll have to rethink how it best serves us. Connectivity and the distraction it enables should be contained. It should be the opposite of frictionless. Imagine the time and focus we could gain!

Naturally, the rural home is ideally suited to this vision. Part of the appeal of leaving the city is the potential to create homes (and lives) that allow for a greater diversity of activities. Working on a laptop might be part of it, but life doesn’t solely revolve around that.

“We do not thrive as parts of a machine. We are intended by nature to be diverse, to do diverse things, to have many skills.” John Seymour

Multiple stories in my book illustrate how things like building a dry stone wall, making a barrel of kimchi or simply learning how to fix a fence become part of daily life alongside creative practices. The process of making is as, if not more important, than the outcome here. These analogue, hands-on activities are grounding exercises in focus and flow. I believe they are crucial for us to process ideas. Our meditation apps might become redundant if we spend half an hour a day actually making something.

Of course, this is also possible in urban environments. From the worldwide boom of pottery to a plethora of workshops teaching fermentation, cider making (a personal ambition) or foraging for wild plants in the city, the desire to make things ourselves and with our own hands is growing everywhere. The rise of repair shops also points to a new, more resourceful mindset emerging. And if allotment waiting lists in London are any indication, subsistence farming is becoming a lifestyle choice again, even in cities. New forms of organisation and alternative food networks make this a viable option.

And it’s fun, too. We only need to fear being replaced by robots, if we live like robots. AI might take over some of our jobs, but I believe it will also lead to a major resurgence of arts and crafts. It might mobilise people in new ways. New luddite rebellion? Bring it on! Not only will we need creativity to find purpose in life (because what are humans for then?), we will also come to cherish the handmade with a renewed sense of reverence. As AI-generated content becomes ubiquitous, ‘made by humans’ will become a quality trademark.

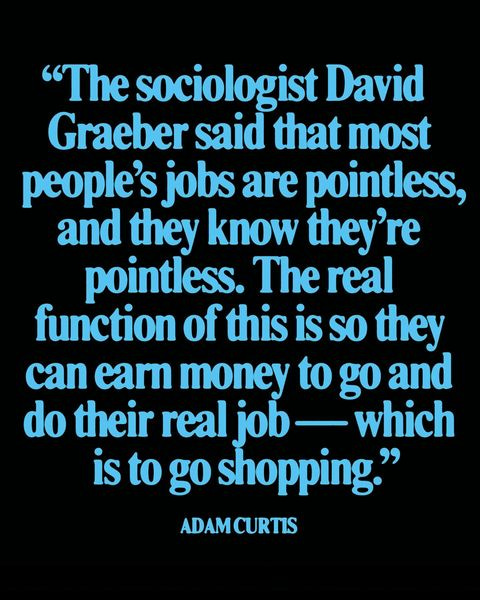

I am excited by the prospect of people scaling back their ‘work work’ in order to do more ‘life work’. Everything we can do to loosen the grip of consumer capitalism on our lives helps us reclaim a bit of autonomy. It might also encourage us to engage with the real cost of the products we buy. Do we understand what really went into producing a phone, a pair of jeans, an apple? The costs to the environment, people and communities that we have externalised and that are neither visible nor accounted for might become more tangible once we learn to make and repair some things for ourselves again. These endeavours become even more empowering if they’re done in community. Total self-sufficiency is hard, and to me also not desirable. The exchange of knowledge, skills, and goods is a vital element of a more equitable and fulfilling future.

Our homes are the places we have the most control over. Let’s start here. Let’s replace personal comfort, convenience and safety with communal vitality, pleasure and agency.

I’ll end with E. F. Schumacher. His words feel as relevant today as they did half a decade ago.

“We can do things for ourselves or we can pay others to do them for us. These are the two systems that support us; we might call them the self-reliance system and the organisation system. All societies support themselves by a mixture of the two systems, but the proportions vary.

Total self-sufficiency is as unbalanced and ultimately stultifying as total organisation. The pioneers show us what can be done, and it is for every one of us to decide what should be done, that is to say, what we should do to restore some kind of balance to our existence.

To grow or make some things by myself, for myself: what fun, what exhilaration, what liberation from any feelings of utter dependence! What an education of the real person! To be in touch with actual processes of creation.”

🕊️

Bye for now. I’m off to chop some wood…

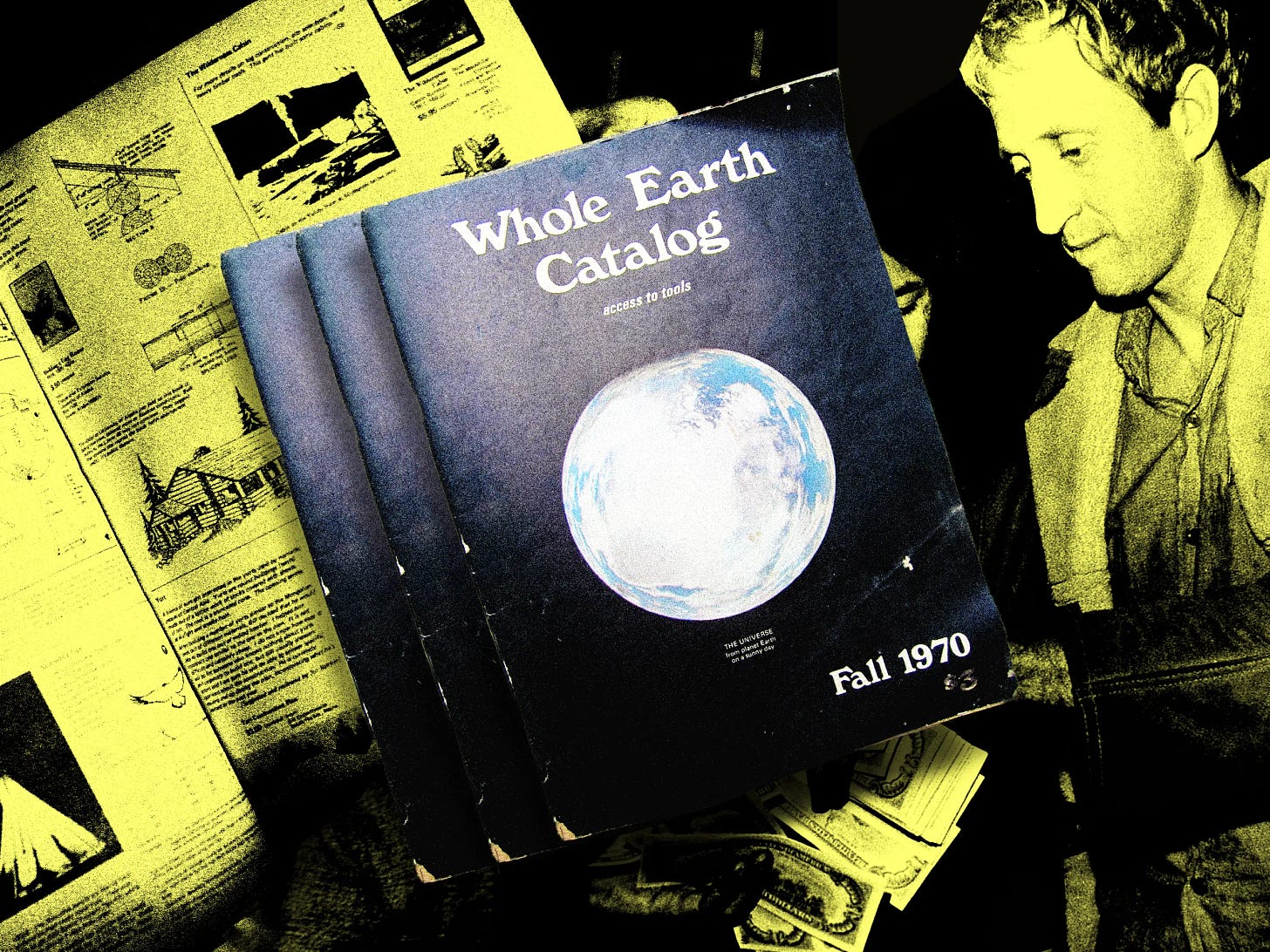

Love this article! I have a picture of the whole earth catalogue in my phone, saw it in a museum once, liked it so much. What I find striking is the obviousness with which technical solutions are being embraced, without reflection, contemplation... do we really need this? In this sense I believe we need more philosophy in our current society. Thank you!

“We only need to fear being replaced by robots, if we live like robots.” I like your refreshing take on AI. Super read, thanks!